There are some fantasy, science fiction, and horror films that not every fan has caught. Not every film ever made has been seen by the audience that lives for such fare. Some of these deserve another look, because sometimes not every film should remain obscure.

Sometimes, though, you do desperately need a rewrite and a few more takes…

The Reptile (1966)

Distributed by: Twentieth Century Fox

Directed by: John Gilling

The best you can say is, the relationship between England and India is complicated.

In 1948, right before India was formally gained her independence, Indian workers were invited to help rebuild the British economy. As Indians came west and put down roots in the UK, English youth coming of age during the post-war years would discover the “Hippie Trail,” and soon the former colony would start to influence the former overlord.

By 1966, this blend would bear out in profound ways. Having been introduced to Indian music during the making of Help!, George Harrison would play sitar on “Norwegian Wood (This Bird Has Flown)”. While not the first instance of Indian influence in British popular music (coming after such pieces as the Yardbirds’ “Heart Full of Soul”), it was certainly a high point in the melding of influences.

On the other end of the scale, meanwhile…

We start with a cold open as we watch Charles Spalding (David Baron) make his way up to the estate of Doctor Franklyn (Noel Willman). He is in the house long enough for something to attack him, after which his venom-filled corpse is taken by an unnamed man (Marne Maitland) and dumped in the village square.

After a brief funeral witnessed by publican Tom Bailey (Michael Ripper) and colorful character Mad Peter (John Laurie), we watch as Charles’ brother Harry (Ray Barrett) and his wife Valerie (Jennifer Daniel) receive the deed to Charles’ home in the reading of the will. The couple arrive in Cornwall to a less than warm welcome from the villagers, and their nasty encounters with Doctor Franklyn do nothing to repair the damage done here to this town’s reputation.

Of course, nothing is quite what we see; the townies don’t welcome the new folks in because too many people are dying of the “Black Death,” the name they’ve given to the affliction of the bitten, and they don’t want to get too attached. Tom and Mad Peter do try and roll out the welcome wagon, though, and the surprise the Spaldings get when Doctor Franklyn’s daughter Anna (Jacqueline Pearce) insist that they come up for dinner looks like things are starting to turn around for the couple.

At least, until Anna starts playing the sitar for them:

As Harry Spalding enlists Tom’s help in getting to the bottom of the matter, we discover Doctor Franklyn’s motivation: he and his daughter Anna are just as much victims here as anyone else for having tried to learn too much from the East.

Suddenly, everything we thought we knew is wrong; considering how badly we were informed before now, could you blame us? Going back to look at the film a second time, you start to pick out the true motivation behind these characters, but you have to work harder than necessary to find them on the second pass. The lack of any subtlety whatsoever in Willman’s acting in the early going makes you have to look more intently than you should to accept the big twist, and if you have to work that hard to read between the lines forearmed the second time out, the fault lies with them, not us.

Maybe we were never going to have this unfold in a satisfactory manner, no matter how much we deserved it to. Hammer Films made the movie right immediately after wrapping work on The Plague of the Zombies, almost simultaneously, in fact; both films shared directors, sets, and a good portion of the cast, with Pearce playing the nightmare inducer in both pics. (On the plus side, her playing two separate antagonists back-to-back was good training for the role she is best known for, Servalan on Blake’s 7.)

Frustratingly, Hammer Films ended up making many of the same mistakes they made two years earlier on The Gorgon, though this time with a smaller budget. It’s the repackaging of a creature that we’ve otherwise seen before, a “were-snake”-ish thing that, other than its bad makeup, doesn’t have any outstanding memorable characteristics, once again running around in a costume drama with familiar beats. Audiences were getting too many of those from the studio, and Hammer was just not striking a cord with them.

We might likely forget this one, too, were it not for the uncomfortable timing of its release. With Calcutta-born Marne Maitland playing the personification of the evil of the East, which pretty well describes most of his CV, the film played up the darker aspects of what the West  thought of that region. At the same time that the West was being introduced to Indian music by the Beatles, some Britons were openly racist to Indians in their midst; legislation to address this behavior would not be passed by Parliament until 1968, and even then the work for a more tolerant society would have to continue for at least fifty years.

thought of that region. At the same time that the West was being introduced to Indian music by the Beatles, some Britons were openly racist to Indians in their midst; legislation to address this behavior would not be passed by Parliament until 1968, and even then the work for a more tolerant society would have to continue for at least fifty years.

Unlike the movie, which was rushed to be released unfinished, we still needed a few more takes and a few more drafts to come to a place where we can truly accept others. Would that we were closer to that day than we are now…

NEXT TIME: Have you seen Mick Jagger’s first film, standing in the shadows…?

The post FANTASIA OBSCURA: Hammer’s Spooky Snake-Woman Supplies Some Slippery Scares appeared first on REBEAT Magazine.

The Monkees have finished fixing Crumpet’s racing car, and Davy takes it upon himself to be the driver for the big race since he is a British subject.

The Monkees have finished fixing Crumpet’s racing car, and Davy takes it upon himself to be the driver for the big race since he is a British subject.

the intent. The studio, during the chaotic time it found itself in when it released

the intent. The studio, during the chaotic time it found itself in when it released  In 1955, a little black-and-white B-movie hit cinema screens and helped change music forever. Blackboard Jungle starred Glenn Ford as a teacher trying to make changes in a inner-city school — a theme not unusual now but ground-breaking then.

In 1955, a little black-and-white B-movie hit cinema screens and helped change music forever. Blackboard Jungle starred Glenn Ford as a teacher trying to make changes in a inner-city school — a theme not unusual now but ground-breaking then.

When Haley recorded “Rock Around the Clock,” he had already released numerous singles, first as a country artist with his band the Saddlemen and then, after a name change in 1952 (inspired by Halley’s Comet), with the Comets.

When Haley recorded “Rock Around the Clock,” he had already released numerous singles, first as a country artist with his band the Saddlemen and then, after a name change in 1952 (inspired by Halley’s Comet), with the Comets.

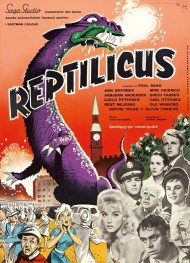

Pink’s hosts, as his ineptitude with setup, pacing, crowds, actors, puppets, you name it, showed in every shot. It was so bad that American International refused to release it without major edits and re-dubbing the phonetic English the crew read their lines with, replacing them with American voice-over artists, and making the edits and additions noted above.

Pink’s hosts, as his ineptitude with setup, pacing, crowds, actors, puppets, you name it, showed in every shot. It was so bad that American International refused to release it without major edits and re-dubbing the phonetic English the crew read their lines with, replacing them with American voice-over artists, and making the edits and additions noted above. brie, love to cite Reptilicus as the best of the worst, the “go-to” example of how low you can sink and yet find joy that far down. In some ways, the film wears its limits like a badge of honor; clips of the movie have appeared in The Monkees, The Beverly Hillbillies, and South Park whenever the script calls for “bad monster movie playing on TV” to be shown. And the movie had the dubious honor of being

brie, love to cite Reptilicus as the best of the worst, the “go-to” example of how low you can sink and yet find joy that far down. In some ways, the film wears its limits like a badge of honor; clips of the movie have appeared in The Monkees, The Beverly Hillbillies, and South Park whenever the script calls for “bad monster movie playing on TV” to be shown. And the movie had the dubious honor of being

Lawrence goes there to meet the professor, who is attended there by his daughter Enid (

Lawrence goes there to meet the professor, who is attended there by his daughter Enid ( Lawrence, the only one of the four not now working for the man (from Planet X), finds his way to the village, where he has to convince the skeptical populace that they’re in danger. They’re already on edge, as some of their numbers have disappeared out in the fog. (One of the scarred people was TV mainstay

Lawrence, the only one of the four not now working for the man (from Planet X), finds his way to the village, where he has to convince the skeptical populace that they’re in danger. They’re already on edge, as some of their numbers have disappeared out in the fog. (One of the scarred people was TV mainstay

things going. There’s major changes in tone between stretches when the alien is behaving in a sympathetic manner, and when he’s more hostile, but both contain enough interesting ideas in them to keep you from tuning out.

things going. There’s major changes in tone between stretches when the alien is behaving in a sympathetic manner, and when he’s more hostile, but both contain enough interesting ideas in them to keep you from tuning out.

Furious at the rejection, Willus seeks out Doll Man (

Furious at the rejection, Willus seeks out Doll Man (

both

both

This horrifyingly cheesy (#SorryNotSorry) film that feels like a made-for-TV production that got into the theaters by mistake actually gave Michael Jackson his first solo hit, by avoiding any mention of rats whatsoever in the lyrics. In avoiding association with the film, the song thrived on its own and did very well by itself.

This horrifyingly cheesy (#SorryNotSorry) film that feels like a made-for-TV production that got into the theaters by mistake actually gave Michael Jackson his first solo hit, by avoiding any mention of rats whatsoever in the lyrics. In avoiding association with the film, the song thrived on its own and did very well by itself.

This is one of the worst examples of extreme sexism ever offered, one where women with extraordinary abilities, like being the only ones to carry Earth’s flag to the stars and form the core of an efficient counter-intelligence agency that keeps us safe, all of that is just accessories the babes are made to wear while they shut up and smile. These accomplishments? That’s nice, honey, now get me a drink and sit on my lap like a good girl, you…

This is one of the worst examples of extreme sexism ever offered, one where women with extraordinary abilities, like being the only ones to carry Earth’s flag to the stars and form the core of an efficient counter-intelligence agency that keeps us safe, all of that is just accessories the babes are made to wear while they shut up and smile. These accomplishments? That’s nice, honey, now get me a drink and sit on my lap like a good girl, you… In 1971, Sun Ra’s journey, which included proclaimed trips to Saturn as well as documented long residences in Chicago, New York, and Philadelphia, during which time he formed the

In 1971, Sun Ra’s journey, which included proclaimed trips to Saturn as well as documented long residences in Chicago, New York, and Philadelphia, during which time he formed the

In 1977 two space probes,

In 1977 two space probes,

Although “Johnny B. Goode” was written in 1955, Berry didn’t record it until 1958 and surprisingly the man who inspired the title of the track didn’t play on the song. Instead it featured regular Chess Records musicians Lafayette Leake on piano, Fred Below on drums and the legendary blues musician Willie Dixon on bass.

Although “Johnny B. Goode” was written in 1955, Berry didn’t record it until 1958 and surprisingly the man who inspired the title of the track didn’t play on the song. Instead it featured regular Chess Records musicians Lafayette Leake on piano, Fred Below on drums and the legendary blues musician Willie Dixon on bass. hear Berry’s lick that sounds “just like a-ringing a bell.” No wonder then that the NASA scientists behind the Voyager spacecraft decided that the song should be extraterrestrial life’s first introduction to the wonders of rock ‘n’ roll.

hear Berry’s lick that sounds “just like a-ringing a bell.” No wonder then that the NASA scientists behind the Voyager spacecraft decided that the song should be extraterrestrial life’s first introduction to the wonders of rock ‘n’ roll.

Christopher Lee, he’s not entirely inept either. The fact that there are people who are better actors than singers who have done more painful vampire depictions gives him something that he need not have been ashamed of.

Christopher Lee, he’s not entirely inept either. The fact that there are people who are better actors than singers who have done more painful vampire depictions gives him something that he need not have been ashamed of.